Commonplace Books and Teaching Pre-1800 Literature & Archives at UMD

By Karen L. Nelson, University of Maryland

Since 2020, I have used commonplace books as an assignment in six upper-level English courses (four iterations of a literary archival research methods course, English 460; Multimedia Shakespeare, English 308A, and Shakespeare: Early Works, English 403, all of which targeted an enrollment of twenty to twenty-five students. You can visit the course archive here). As a person with a twelve-month full time administrative appointment, the teaching I do is in an overload, adjunct capacity. I tend to provide courses that fill instructional gaps, and often receive the invitation to teach a few days or weeks before the semester begins.

I was first introduced to pedagogies associated with commonplace books in the 1990s as a component of a rhetorically-based introduction to academic writing syllabus, but had set aside the practice because its connections to the work of that class seemed tenuous at best and tedious for students to write and me to assess. However, my more recent attempts to incorporate it into upper-level pre-1800 English literature courses suggest myriad benefits. I use commonplace books to help students consider sites of local production, networks of circulation, and differences between manuscript and print circulation. In addition, they show students how editors make choices to include or excerpt materials for miscellanies, anthologies, editions, and adaptations. Commonplace books also help me demonstrate the ways that individuals construct systems for organizing information and base these structures on all sorts of hierarchies and cultural assumptions. Finally, they help students develop skills as content producers and engaged readers.

In my upper level English courses, commonplace books make their first appearances as a first day exercise in which we add a decorative cover of mulberry paper to unlined blank books bound in plain brown paper. I describe the workshop more fully here. At its most basic level, this first-day activity also allows students to begin to learn terminologies associated with book arts —"signatures,” “end papers,” “binding,” and related terms emerge from this conversation and begin a strand of book history to which we return throughout the semester. One related activity that builds on the material culture of the book emerged from the resources for Shakespeare in Sheets, a project from the Illinois State University that reproduces foldable facsimiles of broadsides for classroom use; since the UMD archives include a Banneker almanac, I’ve modified their model to build on the digitized version of the 1793 Banneker almanac (described here). These projects allow students to understand the physical resources of type and paper required, and the technical knowledge needed, to produce even one small volume. Working with these books printed before 1800 also helps students see how much editorial intervention occurs between a primary text and a modern edition.

While students manipulate the books and paper and glue to cover their journals that first day, I talk about the ways that readers in the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries made use of similar volumes to track, collect, and digest their own reading. I show examples of various sorts of compilations such as Andrew Maunsell’s Catalogue of English Printed Books (1595), and connect the tradition to early modern conceptions of invention and copia as well as to commonplaces themselves. (One example of those overviews, “Commonplaces and Commonplacing,” is included below). While we rarely delve deeply into these contextual, archival materials, the students see the connections to a longstanding set of methods for active, engaged reading, as potential sources for their own research and writing.

Our actual implementation of the books in classroom practice is less structured. I recommend students use the books as reading journals, to serve as a place to house responses to reading and to the discussion questions set for the class, to sketch relationships between characters or ideas for a scene in a play. A colleague, David Wyatt, suggested an assignment in which students track a word over the course of the semester; we usually use the Oxford English Dictionary Online early in the semester as we acclimate to primary texts, so the word they identify for that class is one of a few for which they note instances of use as we move through the remainder of the semester’s reading. Some groups use their reading notes to review for midsemester and final exams; others compare artistry if they’ve imagined graphic adaptations of literary texts or staging ideas for the plays we’re reading. Some semesters, students want to share theirs at the end; one semester, they gathered poetry they’d found into an online miscellany (see English 460, spring 2020, below). The books themselves offered a lifeline in the spring of 2020, when we pivoted to online learning. The tactile volumes linked us to our classroom community in ways that surprised us all.

One ongoing benefit is the way strategies associated with commonplace books allow me to discuss methods from earlier periods, both by way of pedagogical practices and to help students understand the paucity of printed texts. A trip to our own libraries’ special collections offers the chance to see printed miscellanies and anthologies from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, along with almanacs from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Those artifacts serve as a bridge to discussions of books as information resources and limitations to access, especially in the context of the mid-Atlantic region pre-1800. Students imagine the parallels to their own efforts to capture materials or events with their phones and begin to understand the complexities associated with knowledge production and dissemination before the internet and computerization transformed the landscape. They comprehend the choices that editors and compilers make as they see the different sorts of materials gathered together.

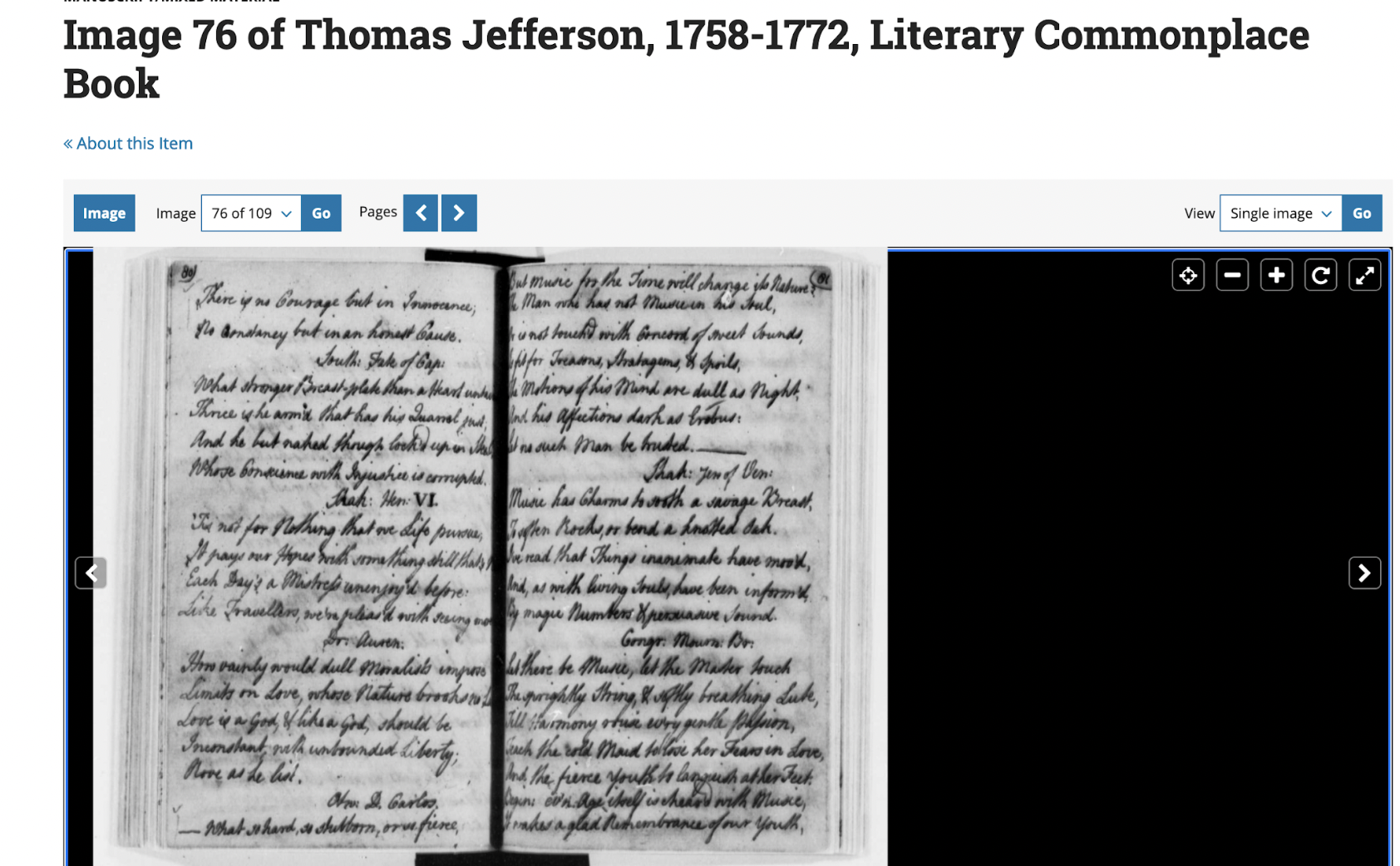

Commonplace books also allowed one class to assess Thomas Jefferson’s literary commonplace book, especially its categories for sorting information, and set those against the hierarchies built into the Library of Congress subject headings, since that collection’s roots are in Jefferson’s library. Such an exercise fostered a discussion of how we access and catalog information, and illuminated some of the assumptions behind and enfolded into our own “comprehensive” searches to demonstrate what search engines are designed to uncover and where their gaps emerge.

Across these courses, and in the ones I design and develop going forward, the commonplace book and its materiality help shape my pedagogical practices and our shared inquiry. As students embrace makerspaces, investigate production mechanisms associated with writing and printing, and develop their skills as content creators, these assignments inform the sorts of research questions we ask in ways that are enormously evocative.

Resources:

Jefferson, Thomas. Jefferson's Literary Commonplace Book. Ed. D. L. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1989.

Jefferson, Thomas. Thomas Jefferson's Library: A Catalog with the Entries in His Own Order. Ed. James Gilreath and Douglas L. Wilson. Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 1989.

Maunsell, Andrew,d.1595. The First Part of the Catalogue of English Printed Bookes Vvhich Concerneth such Matters of Diuinitie, as Haue Bin either Written in our Owne Tongue, Or Translated Out of Anie Other Language: And Haue Bin Published, to the Glory of God, and Edification of the Church of Christ in England. Gathered into Alphabet, and such Method as it is, by Andrew Maunsell, Bookeseller. London: 1595. https://archive.org/details/bim_early-english-books-1475-1640_first-part-of-the-catalo_maunsell-andrew_1595/page/n275/mode/2up

Nelson, Karen. Archives. Includes course websites, workshop information, and additional teaching resources. https://sites.google.com/view/nelsonk365archives/home

-----. “Commonplaces and Commonplacing,” for English 403, spring 2024. https://new.express.adobe.com/webpage/AGWUk2fZbV4Mz

-----. Course site: English 403, spring 2024: Shakespeare: Early Works. https://sites.google.com/umd.edu/umdengl403sp2024/home

-----. Course site: English 308E, fall 2o23: Multimedia Shakespeare. https://sites.google.com/umd.edu/engl-308e-multimedia-shx/home

-----. Course site: English 460, fall 2021: Literary Archival Research Methods: Sustainability in C18 Transatlantic Literature. https://sites.google.com/umd.edu/umd-engl460-f21/home

-----. Course site: English 460, spring 2020: Literary Archival Research Methods: Imagining America vi C18 Literature. https://sites.google.com/view/engl-460-spring-2020/home. Includes a student-created Poetry Miscellany, here: https://sites.google.com/view/engl-460-spring-2020/projects/poetry-miscellany

-----. “Foldable Banneker Almanac, 1793,” based on digital version from the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History & Culture. https://english.umd.edu/sites/default/files/2020-07/2020.02.18_banneker_almanac_printable.pdf

link: https://sites.google.com/view/nelsonk365archives/home

About the Author

Karen Nelson is Director of Research Initiatives and Co-Director of the Center for Literary & Comparative Studies in the Department of English at the University of Maryland. Nelson serves as editor for the Sixteenth Century Journal. Publications include articles on Edmund Spenser, Robert Sidney, William Shakespeare, and early modern women writers, and four edited and co-edited collections on early modern women's lives and works. You can visit the resources on her teaching website here.