“A Salad of Many Herbs”: The Use of Commonplace Books with Undergraduates

By Liz Bloodworth and Joanne Diaz, Illinois Wesleyan University

For early modern writers, commonplace books functioned as thesauri, or store-houses, for memory. We think of sampling as a postmodern practice, but early modern writers were constantly lifting, cutting and pasting, and referring to work beyond their own borders. As William Engel has observed, this kind of collecting of information “served as an aid to gain access to knowledge; not only knowledge of ideas and arguments to be called on for future use, but also of the internal and intellectual constitution of the person compiling and arranging the knowledge.”[1]

In the Renaissance, commonplace books were purchased as blank paper books, and then the owner would fill them with their favorite sayings, quotations, poems, instructions, recipes, songs, prayers, and anything else they wanted. Most of the material in a commonplace book would have been copied from other sources, though of course the compiler could edit copied material and write new material his or herself. Leonardo da Vinci’s zibaldones (“heaps of things” or “salads of many herbs” in Italian) are perhaps the most famous example of this tradition, but many authors, including John Milton and Lewis Carroll, kept commonplace books that reveal a great deal about their creative processes.

Fig. 1: Pages from Leonardo da Vinci’s Codex Forster 1 zibaldones. Victoria and Albert Museum, https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/explore-leonardo-da-vinci-codex-forster-i#?c=&m=&s=0&cv=14&xywh=-258%2C-700%2C3337%2C2685

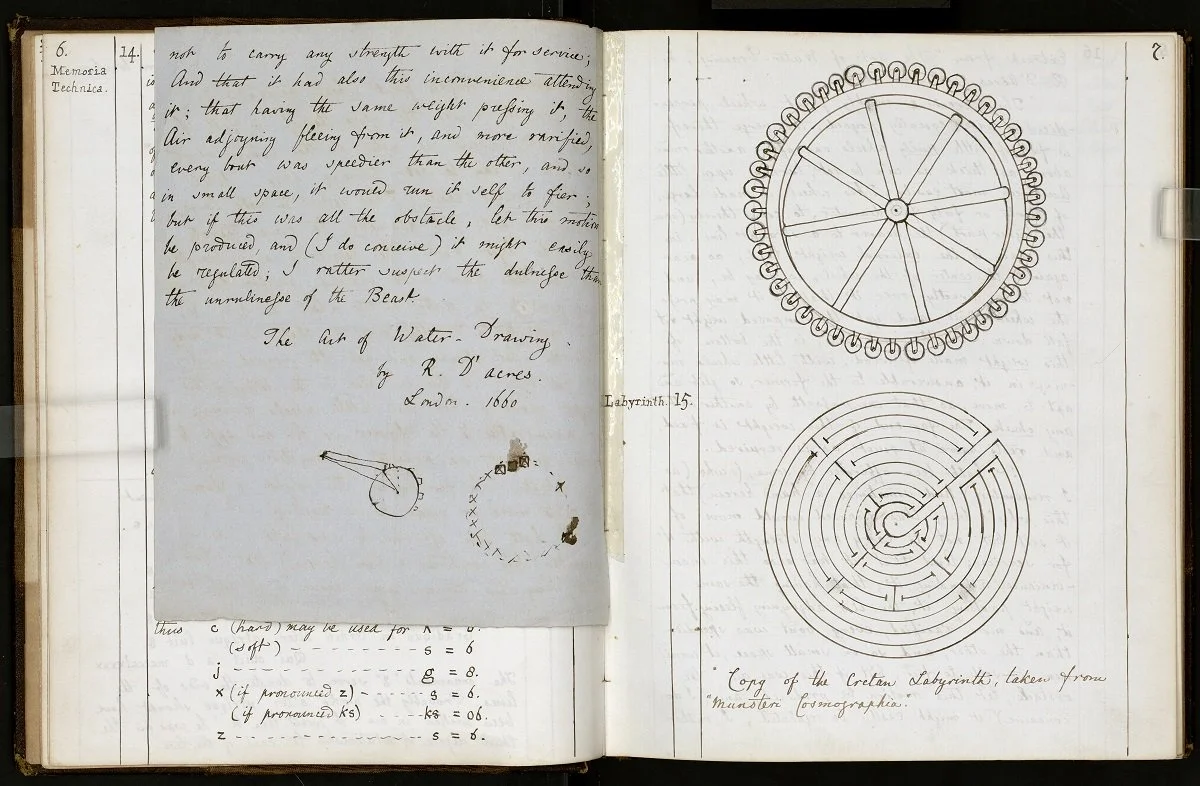

Fig. 2: Pages from a commonplace book kept by Charles Dodgson (better known as Lewis Carroll) with information about ciphers, anagrams, stenography, and labyrinths. https://sites.utexas.edu/ransomcentermagazine/2015/06/09/social-media-nothing-new-commonplace-books-as-predecessor-to-pinterest/

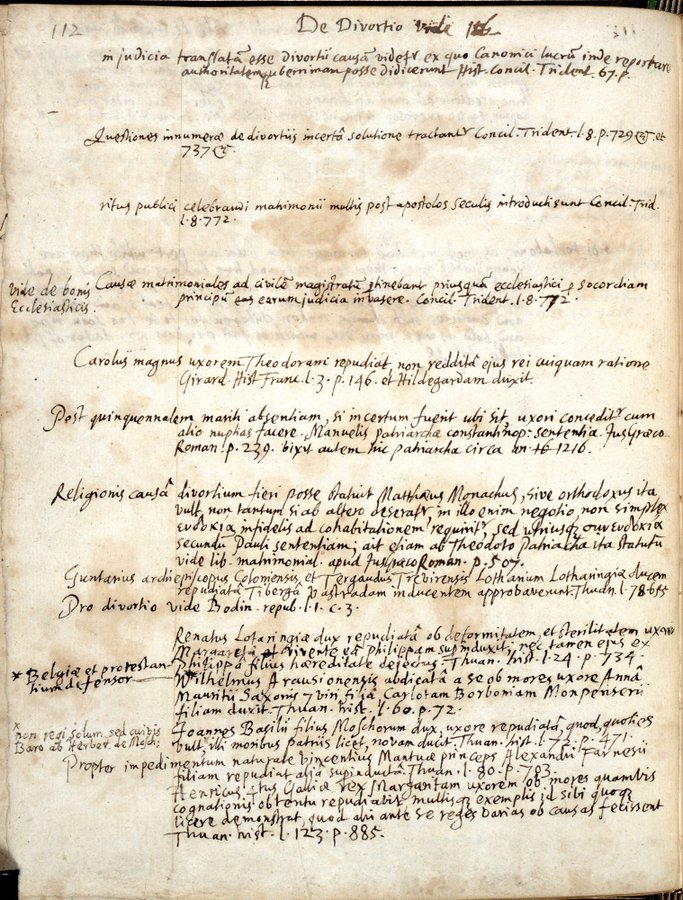

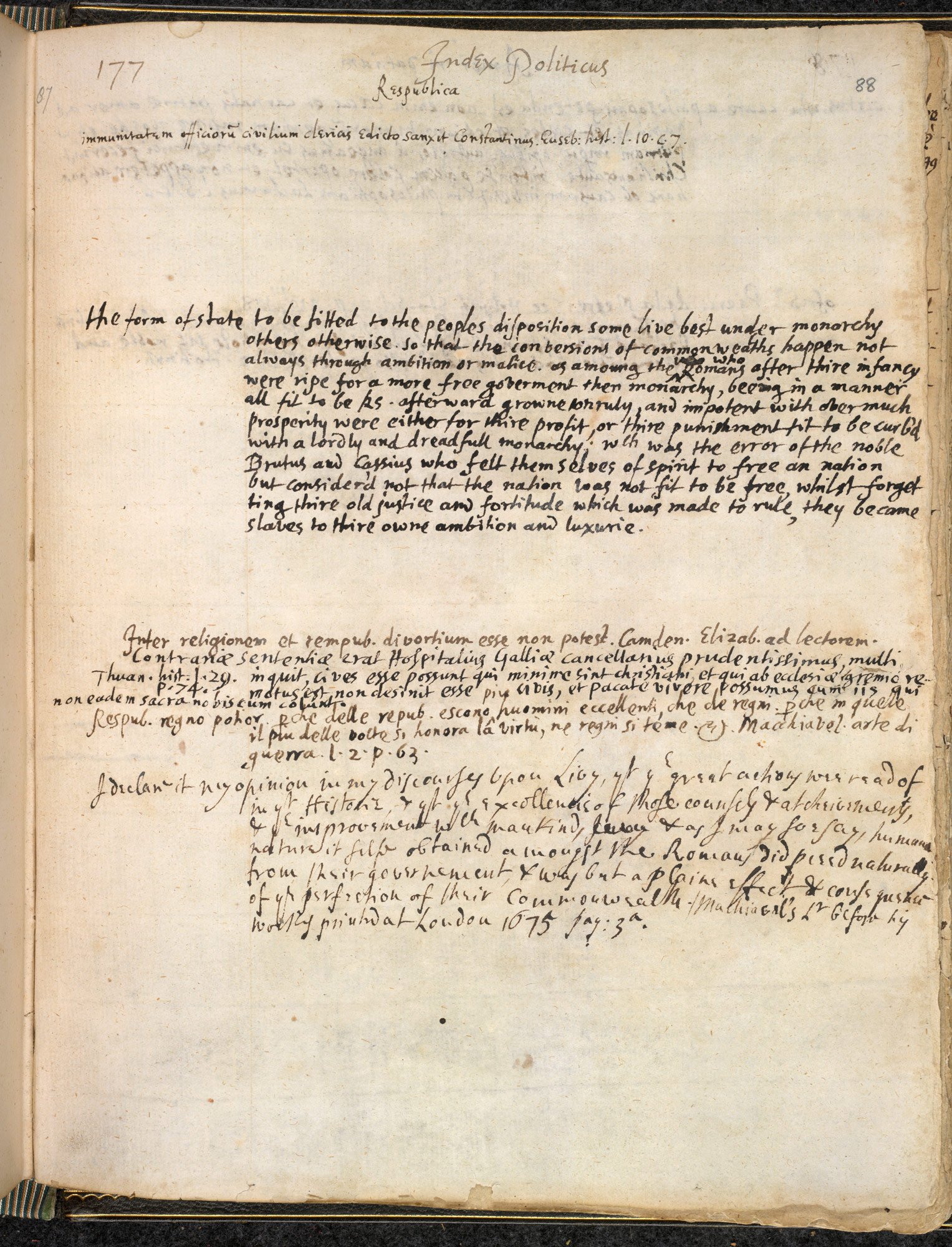

Fig. 3: Pages from John Milton’s commonplace book. British Library, https://x.com/britishlibrary/status/1395291972135497730/photo/2

At a liberal arts college like Illinois Wesleyan, students in small, discussion-based seminars are in a unique position to engage with this tradition. In a class called Survey of English Poetry, 1500-1700, students regularly write and sketch in small, unlined Moleskine notebooks during the course of the semester. Then, in the final weeks of class, they visit the archives multiple times to create an exhibit that showcases both material from IWU’s Tate Archives & Special Collections as well as commonplace books created by their classmates throughout the semester. Though the archives houses just a single item categorized as a “commonplace book,” it contains related types of material, ranging from scrapbooks to diaries to class notebooks. As Zboray and Zboray point out, overlap exists across formats:

While the folks who created these literary items recognized each one’s distinct form and purpose (the diary to record daily events, the commonplace books to transcribe extracts from printed matter, the household account book to track expenses, and the scrapbook to house clippings), in practice they often merged formats, so that a diary, for example could easily morph into a scrapbook or a scrapbook into a commonplace book.[2]

Accordingly, during the Fall 2023 semester, the first class visit focused on exposing students to diaries, scrapbooks, and notebooks alongside the more traditional commonplace book to offer them the chance to observe the similarities firsthand. During this initial introduction to archival holdings, the students interacted with material dating back to the mid-nineteenth century and learned more about how the practice of commonplacing has evolved over time.

Fig. 4: University Archivist and Special Collections Librarian Liz Bloodworth introduces students to commonplace books and notebooks in the collection.

In subsequent trips to the archives, they made connections between archival material and their own commonplace books and selected items to feature in their exhibit. Items chosen included a Civil War diary kept by early IWU President William H. H. Adams and a scrapbook assembled by IWU alumna Florence Kasiske (Class of 1933).

Fig. 5: A page from IWU alumna Florence Kasiske’s scrapbook.

Once selected, the students then learned about the process of telling a story through exhibit labels and promotional materials. In addition to writing labels, students created flyers to advertise on campus and on social media. During their final visit on Wednesday, December 6, 2023, the students installed the exhibit in the rotunda cases on the entry level of the Ames Library.

Fig. 6: Students from Survey of English Poetry, 1500-1700 install the exhibit in the rotunda of the Ames Library at Illinois Wesleyan University.

Through this exercise, students had the opportunity to interact with archival material, while learning about the process of exhibit curation and connecting with university history. Assembling an exhibit facilitated student growth in the primary source literacy skills of interpretation, analysis, and evaluation by assessing “appropriateness of a primary source for meeting the goals of a specific research or creative project.”[3] In this case, the goal was to relate their coursework to historical artifacts in order to tell a meaningful story about the practice of commonplacing. Students made connections by curating pairs of an archival item and a class-made commonplace book. For example, they highlighted autumn leaves affixed to student-created commonplace books alongside a botany notebook kept by a 1928 alumnus.

Fig. 7: A page from Danielle Huber's commonplace book.

Fig. 8: A page from Illinois Wesleyan University alumnus William Bach’s botany notebook. Tate Archives and Special Collections, Illinois Wesleyan University.

Another pairing drew similarities between a list of ingredients for a student’s favorite recipe and a list of grocery purchases recorded by a Civil War soldier.

Fig. 9: Pages from a pocket-sized Civil War diary kept by William H. H. Adams, who later served as Illinois Wesleyan University president. Tate Archives and Special Collections, Illinois Wesleyan University.

Creating these pairings for the exhibit demonstrated an understanding of the relationship between their coursework and the historical practice of recording ideas and experiences. Perhaps even more important, though, the practice of keeping a commonplace book allowed them time to copy and remember lines of Renaissance poetry, sketch objects from their daily lives, and slow down in an otherwise busy world. In fact, in their course evaluations, several students noted that keeping a commonplace book was their favorite part of the semester, and some students say that they will continue to keep a commonplace book in the future.

Notes

[1] William Engel, The Rhetorics of Life Writing in Early Modern Europe (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1995), 283.

[2] Ronald J. Zboray and Mary Saracino Zboray, “Is It a Diary, Commonplace Book, Scrapbook, or Whatchamacallit? Six Years of Exploration in New England's Manuscript Archives,” Libraries & the Cultural Record 44, no. 1 (2009): 102.

[3] SAA-ACRL RBMS Joint Task Force on the Development of Guidelines for Primary Source Literacy, Guidelines for Primary Source Literacy (Association of College & Research Libraries and Society of American Archivists, 2018) www2.archivists.org/sites/all/files/Guidelines%20for%20Primary%20Souce%20Literacy_AsApproved062018_1.pdf.

About the Authors

Liz Bloodworth is the University Archivist and Special Collections Librarian at the Ames Library at Illinois Wesleyan University. Her research interests include primary source literacy instruction, the use of artificial intelligence in archival processing, and methods for building more inclusive archives.

Joanne Diaz is the Isaac Funk Endowed Professor of English at Illinois Wesleyan University, where she teaches courses in literature and creative writing. She is the author of two poetry collections, The Lessons and My Favorite Tyrants, and with Ian Morris she is the co-editor of The Little Magazine in Contemporary America. With Abram Van Engen, she is the co-host of the Poetry for All podcast.